Practical Radicals Ep. 5: Disruptive Movements with Frances Fox Piven + a tribute to Girija Bhargava (1937-2024)

Hi everyone,

As some of you know, Deepak’s beloved mother, Girija Bhargava, died last Friday. As much as Deepak, his father, Madhu, and I had planned for this moment, it has been an overwhelming shock. As Deepak sat by his mother’s hospital bed on her final, blessedly peaceful day, he composed a tribute I’ve posted below. If it were not for the fact that this week’s episode of the Practical Radicals podcast was virtually done, we might have postponed its release today. But we think Deepak’s mom would have wanted our interview with Frances Fox Piven, and her vital message about the power of even the most seemingly powerless people, to come out on schedule, so we begin with that.

In hope and solidarity,

Harry

Practical Radicals Ep. 5: Disruptive Movements with Frances Fox Piven

In this episode, we explore the strategy of disruption and talk with one of its leading theorists and practitioners, the legendary scholar and activist Frances Fox Piven. Stephanie and Deepak begin by distinguishing protest from disruption, two types of action that are often confused. They consider famous instances of disruption, like the mass actions on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation that blocked the Dakota Access Pipeline, and lesser-known ones, like the 1975 “Women’s Day Off” that helped win equal rights for women in Iceland. They also reflect on how overdogs use disruption, citing the “Brooks Brothers Riot,” a protest by GOP operatives that may have tipped the 2000 election and presaged the insurrection of January 6th, 2021. Then, in a wide-ranging interview, Frances Fox Piven argues that “the most important achievement of elites is to persuade people that they don’t have power.” But, she explains, ordinary people in complex societies have enormous “potential power,” the power to disrupt by stopping work, breaking the law, or simply refusing to cooperate. Invoking a chapter of history she and her late husband, Richard Coward, helped write, Piven recalls the Welfare Rights Movement, when poor women of color used their disruptive power to get benefits they had been denied and hugely increased the amount of money spent of welfare in the U.S. Frances, Deepak, and Stephanie also discuss the potential for using disruptive power today, the ways that too much organization can stifle movements, and the essential role of exuberance, ecstasy, and even “sexuality” in movement politics.

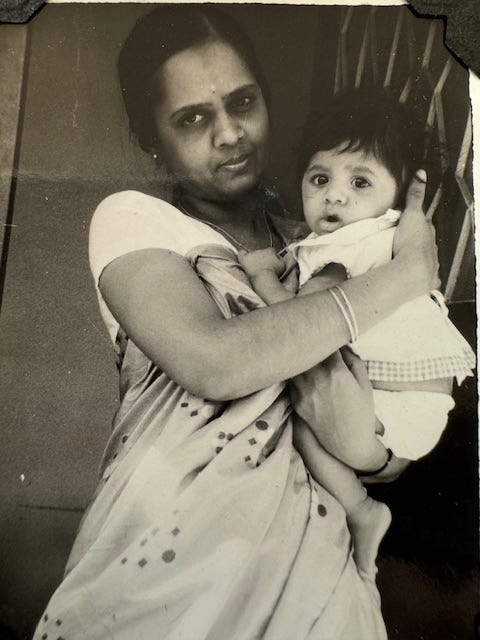

Girija Bhargava (September 8, 1937 – March 22, 2024)

Girija led an extraordinary life. Born in 1937 in Mysore in a family that sometimes struggled to put food on the table, she got a PhD in biochemistry, a rare feat for a woman of her generation. She loved and was loved by my grandmother, Saraswathamma, and grandfather, N.S. Subba Rao, and her three sisters Vimala, Shakuntala, and Vijaya. She spoke often of her mother’s immense generosity and kindness, about how her older sister Vimala was like a second mother, about Vijaya’s good heart, and about Shakuntala’s brilliance as a mathematician. She remained close to all of them until they passed. She adored her beloved nephews Somanath and Ranjan, their wives, kids, and grandkids, and other members of the extended family.

She built a life thousands of miles away in the United States as a research scientist, co-authoring papers titled things like “Crystal Structure of human mitochondrial NAD(P)+- dependent malic enzyme: a new class of oxidative decarboxylases.” There is barely a word in the paper that is comprehensible to me. Dr. Bhargava worked incredibly hard – going to the lab late at night to “feed the cells” while I was a kid and mentoring and encouraging many young immigrants in the sciences. One time, in order to get parathyroid glands from cattle for an experiment, she, a strict vegetarian, had to go to a slaughterhouse in New Jersey and wear knee high boots to wade through blood and stick her hand into cows’ throats for two hours to get ten specimens.

She amazed herself by her ability to adapt to a new country where she didn’t know the culture. She told a story of being stranded in Yellowstone National Park with me as an infant, without any money, somehow managing to make it back to Madison, WI. New to harsh winters, she drove through a snowstorm on Storrow Drive in Boston to pick me up from childcare. She later had to figure out how to fix a broken water heater by herself in the dead of winter in an old house in Newton, MA. She and my father found out about segregation the hard way, driving to many rentals advertised only to find that they were “rented” on their arrival – they would have friends call later the same day, and the apartments would be vacant again. She would, at a time when vegetarianism was eccentric, stop at a Burger King on a highway rest stop and order “a whopper, hold the burger,” producing bemused expressions from cashiers and customers.

There were hard times. Our family struggled financially, but she held us together through grit, extreme thrift, and love. She experienced considerable discrimination as an immigrant woman of color. When she retired, she had several blissful years traveling the world, seeing concerts, and nourishing her friendships before she had a terrible spinal cord injury that left her temporarily paralyzed. While she regained the ability to walk, she lived with chronic pain for the rest of her life and couldn’t pursue many of the activities she had previously loved.

She was with my father for 62 years. They were devoted to each other and cared for each other in ways big and small. My father’s care for her in the 20 years after her spine surgery was one of the greatest acts of love I’ve ever seen. To paraphrase the poet W.H. Auden, for Harry, me, and my dad, but especially my dad: she was our North, our South, our East and West; Our working week and our Sunday rest; our Noon, our midnight, our talk, our song.

Harry and I moved back to NYC when my parents’ health challenges began to increase in 2014, and we’ve had 10 years of living across the street, next door, or three floors down. In a culture where youth flees rather than honors elders, some friends expressed puzzlement at the choice. Even my mother was surprised, noting that this was very traditionally Indian behavior for her Indian-born but culturally American son. The decision to move back was one of the best of our lives, giving us precious time together. Harry and I know that we got far more than we gave.

We would talk to my parents every morning at 8am and see them nearly every day. Harry or I would walk with my mom many mornings and afternoons – these were the routines that structured her days. She would socialize with her neighbors and was beloved as “the Mayor” of the apartment complex we live in. I was always puzzled how she got to know so many people, who would stop by to chat with her when she was sitting in the “dog park” across the street or on a bench in our lobby. She had close relationships with some of the workers in the building too, especially Hamidou, who she adored and often shared newspaper articles with.

After Covid hit, Harry, my great love, quit his job as a teacher so as not to expose my parents, and he took on an even more important role in my mom’s life. She loved Harry like a son, often talking to me about her amazement at his compassion and kindness. Harry was devoted to my mother, and they talked about everything – from politics to music to history. They read history books together, like The Fiery Trial about Abraham Lincoln and the abolition of slavery. Harry cut up books for her when she grew too weak to hold hardbacks. He set her up with Spotify and Audible accounts and a little green bluetooth speaker and headphones. Harry constantly thought of ways to improve her quality of life, from bringing her new music or food to new audiobook and podcast ideas to documentaries and movies. His caregiving was exquisitely tender. Their spirits vibed together on deep planes.

So many memories.

When I was a kid and we were lying together on a bed, I noticed a few spots near her ear, a birthmark. I asked her what they were, and she spun a tale about how she was really a leopard – temporarily taking human form – and her eyes grew big. I loved it.

I competed in a spelling bee in elementary school and flunked in an early round for failing to spell “Wednesday” correctly. She and my father, who had taken off work to come see me, howled at this during the ride home and continued to tease me for years after whenever the word would come up in conversation. None of that “you’re perfect in every way” parenting style from her! Yet, I knew that she was immensely proud of me – she kept press clippings about me and bragged about me to her friends. Despite her injuries, she made a special effort to come to a farewell party for me when I left Community Change in New York City, and got to hear the jazz great Vijay Iyer perform. (Her favorite career highlight was when I got appointed to teach at CUNY, so she could tell everyone her son was a professor, a lifelong dream).

I have so many food-related memories of my mom – how she would cook for me after a long day at work, how she would make care packages for me when I would get ready to take the train back to DC after a visit, how she would bring me samosas when I was on the thousands of conference calls I took from her couch. The taste of her chapatis, her chana, her bhindi, her aloo gobi, her idlis and dosa and especially her upma and her gulab jamun are vivid even now, years after she stopped cooking. Harry and I were pleased that, after a lot of trial and error, we were able to cook dishes for her that she loved.

She made me learn piano and was proud of my paltry accomplishments. She taught me how to ride a bike and how to play tennis, a favorite family pastime (she would describe her style as “moonball tennis”). We went everywhere together, seeing Dave Righetti pitch a no-hitter at Yankee Stadium, and traveling all over the country, often piggybacking on the scientific conferences she went to. She showed me her beloved hometowns, Mysore and Bangalore, and introduced me to our extended family. We all loved the beach and the ocean, and some of my happiest memories are watching her and my dad holding hands, happily tumbling in the waves.

And there were the everyday memories of sitting in the sun in a nearby park, reading companionably or chatting. Going for walks and buying chocolate croissants. Sharing stories of our travels and adventures. Watching MSNBC or Meet the Press.

She made friends easily, and they adored her. Her best friend, Marie Daley, was an acclaimed scientist and a Black woman, at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, where my mom worked for many years. Across considerable cultural distance, they had a friendship based on the challenges they faced as women of color in the sciences and a shared love of the arts. My mom would often visit Marie, in Florida or in Sag Harbor.

She kept making friends until the very end. Over the last two years, she grew close with Shahrzad, a 25-year-old friend and colleague, who came and housesat for us and who she found delightful, kind, and fascinating. (I think my mom saw herself in Shahrzad.) Over the last year, my mom struck up a friendship with a neighbor, Krutika, who she taught Kannada to (mom spoke 5 languages), and with a caregiver Malia, with whom she would blast music of all kinds in the park next door. She loved kids, particularly little ones (before they could talk back too much, she said), and befriended so many in our neighborhood and building. She would give toy trucks to Mark and Steven, two of her favorites whom she watched grow up, and she had a delightful reunion with them (both formidable athletes now) last summer in the park across the street from our house. She delighted in seeing Juliette and Josephine, daughters of our neighbors and friends Bruce and Magalie, grow up to be extraordinary young women. She delighted in visits from our friends Alisa and Mike, Christian and Megan, Akwe, Dorian, Oxiris, Sung E, Will, and Zoe, and our friends’ kids, including Deva, Milo, and Oscar.

I have met few people in my life with such a zest for life. She loved to chat – calling this the Mysorian way of life. Her passion for music was boundless. She herself had a beautiful voice and took voice lessons when she was young. She listened to everything, from Indian classical to western classical, from jazz to country. Harry laughs about how he walked in one morning to find Metallica blaring from her stereo. Our godson Oscar, visiting from Spain, came down after spending time with her, astounded that she was a big Kendrick Lamar fan. (She was “so cool,” he said, implying correctly that she was hipper than we were.) She was intrepid – traveling to Italy, Hawai’i, and Spain in her retirement, and seeing concerts and plays in Central Park and downtown. (She was a master of how to see great stuff for free in NYC.) Harry’s music teacher, Luca, came to play Chopin, Liszt, and Mozart for her a few times in my parents’ apartment, long after she was able to go out to hear live music, and she was ecstatic, reveling in the beauty, transported to another dimension. She loved to read and listen to books, devouring the New York Times, magazines like The Atlantic and The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, and pretty much any audiobook about Trump’s crimes and venality.

Her character was defined by several abiding qualities. Her capacity for love and her generosity were immense. Her hatred of cruelty in all its forms was profound, whether it was the unjust killing of Black people by the police, the mistreatment of workers in India or in the U.S., or the mass death in Gaza. She was proud to have marched in Central Park against apartheid. From her, I acquired an abiding and instinctive sense of identification with underdogs of all kinds, and a fierce dislike of bullies. Her political views were not derived only from the intellect – they were rooted in her heart, guts, and lived experience. There was a streak of defiance and independence too. She was stubborn and had a temper that rarely showed but was fearsome when it did. She prized her independence and her dignity, and it was often hard for her to be dependent on others for her care. She was a hardheaded pragmatist and stoical realist about most things, though she for many years went to spiritual talks at a nearby center and we mused together about the meaning of life and what comes after.

This last week was full of hard stuff, but there were moments of grace too. A string quartet was playing at the hospital, and Harry asked the cellist to come to her room and play a Bach cello concerto and The Swan by Saint-Saëns (my mom, Harry and I had watched The Swan in a performance by Yo-Yo Ma and L'il Buck that thrilled her). We were able to read notes from friends as she came in and out of consciousness, and to play a song Deva recorded especially for her, which delighted her. Krutika wrote from Bangalore and attributed her improved Kannada to my mother’s instruction. And in her last lucid period, she let loose with wisdom in breathless short sentences like, “You come, you enjoy life, you go,” and “Everything on this earth is temporary.” About western medicine’s preoccupation with extending life beyond good sense, she said, “The Indian way is better.” She summed up her own life with satisfaction: “I did everything.” Some of her final words said it all: “Love you! Bye.”

One of the many profound lessons I take from my mom’s extraordinary life is that we can always orient towards joy, love, pleasure, and community – our human birthrights – even in difficult circumstances.

For me, her love was like a steady fire, bathing me in warmth, security, and confidence. It was love beyond cause and conditions, a fire that I knew would never go out, no matter what. And even though she’s gone, I can still feel the fire. Yesterday, when I told her I loved her for the millionth time, she said “I love you more” – the line she’s used with me for decades, blessing me one last time with her signature knowing and joyous smile.